Before the Knock on the Firehouse Door

There was a time when every firehouse looked and felt the same. You could walk into any station in North Texas and find the same smell of rubber and coffee, the same wall of turnout gear, and the same sound of a table being slammed mid-domino match. It was all familiar — and predictably, all male.

At Local 1329, it wasn’t that anyone consciously pushed women away. It’s just that nobody imagined they’d show up. The job was tough, physical, sweaty, loud. It demanded long hours, thick skin, and a willingness to eat breakfast with your boots half on. It was a world built by men, for men, and for a long time, nobody really questioned that.

So when folks say “the first woman firefighter,” it sounds like a headline. But the real story began long before she ever walked in the door. It started in the cracks — subtle shifts in the air as younger firefighters came up through the academy, bringing different ideas. It started in the quiet, off-duty conversations some of us had, wondering why the department had never hired a woman. Not accusing, just… wondering. The ground was shifting, even if we didn’t know it yet.

There were voices outside the walls, too — daughters asking their firefighter dads, “Why aren’t there any girls on your crew?” Or high school EMT students walking through on career day, eyes scanning the walls, not seeing anyone who looked like them.

Change doesn’t always begin with a protest. Sometimes it begins when a space built for one kind of person finally notices who’s been left out.

Before the knock came at our door, the silence had already started to ask questions.

The truth is, we weren’t fully ready — not culturally, not logistically, not emotionally. But firefighting has never been about waiting until you’re ready. It’s about responding anyway. And the firehouse that once assumed it would always be one kind of family was about to find out that family had room to grow.

Who Was Sara Martin?

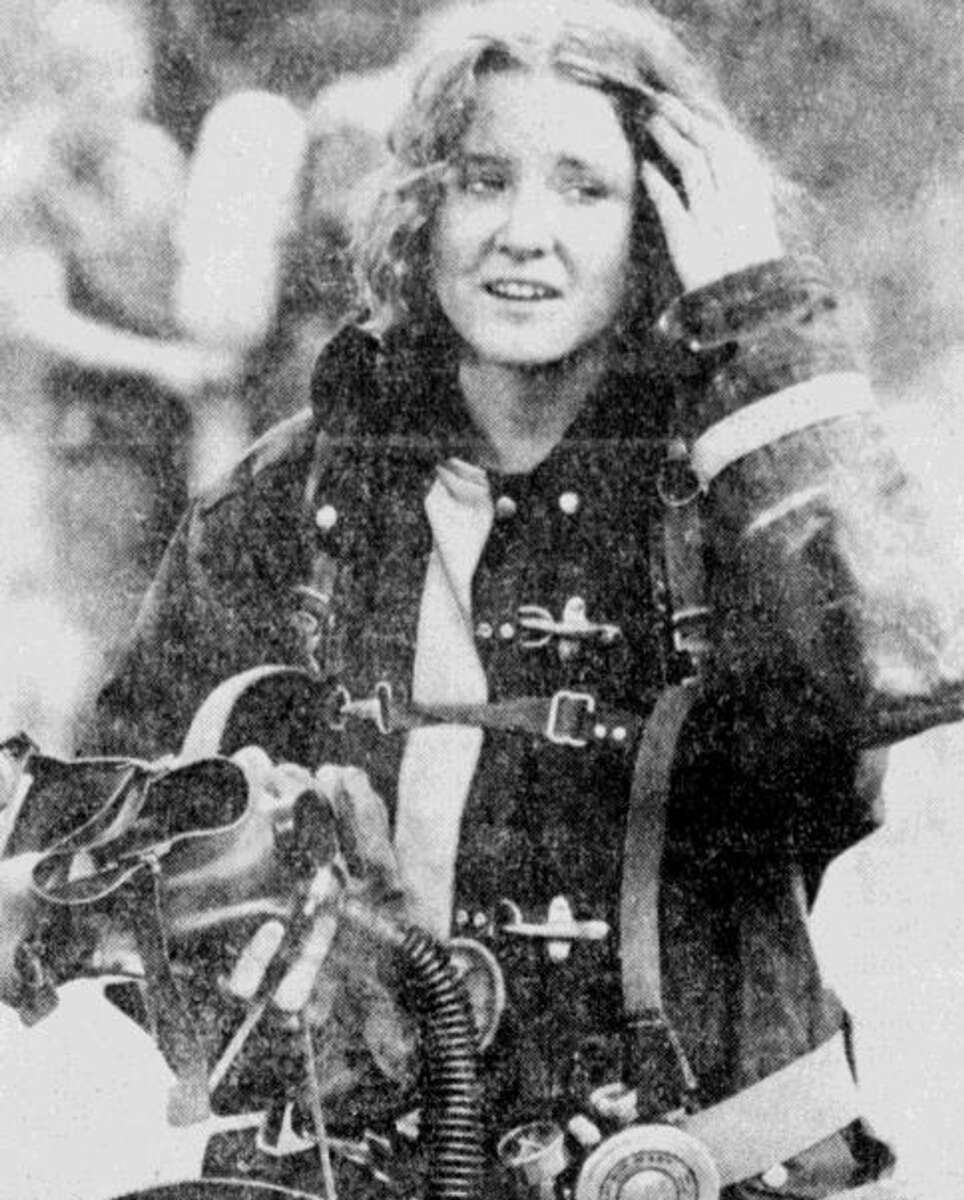

You wouldn’t have picked her out of a crowd.

Sara Martin didn’t carry herself like someone with something to prove. She wasn’t loud, didn’t drop buzzwords, and never once bragged about her fitness scores — though we later found out they were top of her academy class. She stood maybe five-six in boots, lean but strong, with sharp eyes that noticed everything. She listened more than she spoke. The kind of person who kept her back straight, her eyes steady, and her coffee black.

Sara came from Parker County, where she spent most of her youth splitting fence posts and patching barns with her older brothers. Her dad ran a welding business, her mom was a nurse, and by the time she was 10, she could hook up a trailer faster than most grown men. She got into emergency medicine the long way — started as a volunteer medic at rodeos, then spent nights on rural ambulance shifts while studying fire science at a community college that didn’t even offer turnout gear in women’s sizes.

When she applied to Arlington, she didn’t bring a résumé padded with buzz. She brought one with call logs, hours in the field, and handwritten instructor recommendations. One of those notes simply read:

“If you need someone who will show up early, ask hard questions, and outrun your standards — it’s Sara.”

The interview board that day was split. Some saw potential. Others — not yet malice, but uncertainty. She was offered a spot, quietly, without ceremony. No photo op. No newsletter headline. Just an assignment and a locker key.

Her first day, she showed up an hour early, in boots still stiff from the store. She didn’t talk much. Just watched, nodded, and folded into the daily rhythm with the kind of effort that doesn’t draw attention to itself.

But people noticed. How she stayed after drills to reset cones. How she never passed off cleanup. How she took notes after every call, even the slow ones.

There’s one story from her second month that most of us still remember: a kid came by during a station tour, maybe eight years old, tugged at Sara’s sleeve and asked, “Are you allowed to be a firefighter?” Sara squatted down, smiled, and said, “Only if I try harder than the guys.” The room went quiet for a second. Then one of the old dogs in C-shift chuckled, clapped her shoulder, and muttered, “Well, hell, she ain’t wrong.”

That was Sara. Not a headline, not a symbol. Just a damn good firefighter with her eyes on the work and her feet planted firm.

And that was more than enough.

Shifting the Firehouse Current

Culture doesn’t change like a light switch. It shifts like a fire line under your boots — slowly, then all at once.

When Sara joined Station 3, there wasn’t some big meeting to prep the team. No policy memo. No “how to work with women” handbook. Just a quiet word from the captain during lineup: “She’s got the same patch on her shoulder. That’s all you need to know.”

But the current under the surface? It started to swirl.

The jokes got… filtered. Not out of censorship, but because folks started noticing what they were saying. The calendar in the locker room came down without a word. The tone in the kitchen softened, especially around the rookies. It wasn’t about walking on eggshells — it was about growing up a little.

Shift dynamics changed too. Sara didn’t try to lead drills, but she ran stairs until her legs burned and then asked if anyone wanted another round. She wasn’t the loudest voice at the table, but when she spoke during post-call reviews, people leaned in. Over time, respect didn’t come from her gender — it came from the way she showed up every single day.

Change didn’t arrive with a lecture. It came in work gloves and a tucked-in shirt, one shift at a time.

There were practical things, too. The bunkroom needed curtains. The shower schedule shifted slightly. Gear sizing became an actual conversation. For the first time, someone asked if all the oxygen masks fit everyone’s face properly — and suddenly, other firefighters realized they’d been tolerating things that didn’t quite work for years.

What surprised most of us was how these adjustments didn’t cause division. They brought cohesion. We started double-checking harnesses more often, running through drills an extra time, and staying sharper across the board. Not because Sara asked us to. But because having her there reminded us that being a better firefighter starts with being a better teammate.

Rookies who came in after her never knew anything different. They arrived into a culture already in motion, one that had a little more patience, a little more professionalism, and — if we’re being honest — a bit more heart.

Looking back now, it’s clear: the shift wasn’t about “accommodating” a woman. It was about maturing as a team. And somehow, that quiet rookie from Parker County made us all better just by doing the job with grace and grit.

Sometimes the most lasting leadership doesn’t come from the front of the room. It comes from the one who keeps showing up, long after others would’ve quit.

The Hurdles No One Sees

There’s a funny thing about “firsts.” Everyone celebrates the title, but few stick around long enough to watch what it actually costs. Sara never once asked to be treated differently — and maybe that’s what made it easy to forget how many little things were quietly stacked against her.

Start with the gear. Her turnout pants were too long. The shoulder seams in her jacket restricted movement when she hoisted a ladder. Her gloves were always just a bit too wide in the fingers. Not enough to seem like a big deal — but enough that it slowed her down when it mattered. For months, she adjusted, adapted, modified, never once asking for replacements. It wasn’t pride. It was a calculation: make do, or be labeled the problem.

The station layout didn’t help either. The bunkroom had no real privacy. The only women’s restroom was technically a guest facility, shared with visitors and sometimes out-of-town crews. Locker space? She got a half-sized cabinet wedged in next to the gear dryer. One time, someone taped up a sign above it that read “Ladies’ Wing” as a joke. It stayed up for weeks.

These weren’t acts of cruelty — just symptoms of a system that hadn’t imagined her existence.

Then came the calls. Not the fire scenes themselves — Sara thrived under pressure — but the people we served. More than once, a resident handed paperwork to another firefighter, assuming he was in charge. On one EMS call, a bystander asked her if she was “just the driver.” And on a mutual aid scene, a visiting firefighter from another department actually said, “I didn’t know you girls did this kind of thing.”

Sara never snapped back. She met ignorance with calm, and disrespect with competence. But that doesn’t mean it didn’t sting.

Even internally, there were subtle tests. Some crews made her run the SCBA maze twice, “just to be sure.” She was routinely assigned hydrant duty, even when she’d proven she could lead interior attack. None of it was written down. It just happened — over and over.

What most people never saw was the mental load she carried. Every word she said was weighed before it left her mouth. Every mistake — and she made few — felt louder because of who she was. There’s a kind of invisible pressure that comes with being the only one of your kind in the room. And she bore it with a kind of quiet courage that most of us didn’t fully understand until much later.

Courage isn’t always dragging someone from a burning room. Sometimes it’s showing up to the locker room — again — knowing you’ll be the only woman there.

But here’s the thing: she never let those hurdles define her. She noticed them, stepped over them, and kept her focus where it mattered. On the job. On the crew. On the next call.

And in doing so, she started clearing the path — not with noise, but with presence.

What She Left Behind

Sara never stayed long enough to become a captain, never wore the white shirt or pinned a brass badge on her collar. She didn’t chase rank. What she built was something quieter — and stronger.

After eight years on the line, Sara took an opening in the training division. It surprised a few folks; many thought she’d eventually run a station. But the truth? She saw where the real shift needed to happen. Not just in policy, but in perspective. She once told me over a bad cup of 4 a.m. coffee:

“It’s not about getting more women in the door. It’s about making sure they stay once they’re here.”

In her new role, she rewrote scenario scripts so they didn’t default to “he.” She pushed for gear evaluations that included non-standard sizing. She sat in on academy panels, not as a token, but as a voice that knew exactly what was waiting for recruits on the other side of graduation.

One of the most impactful things she ever did? She personally called a young candidate — a woman who’d failed her CPAT by less than five seconds — and encouraged her to try again. That candidate passed the next round. She’s now a senior firefighter on C-shift. Ask her why she didn’t give up, and she’ll say: “Sara called me.”

Even now, long after she transferred out of field work, we still feel her presence. The little things add up: the adjusted SCBA policy that accounts for torso length; the academy’s first all-gender locker module; the fact that no one blinks anymore when a woman walks through the bay door.

At Station 3, there’s still a helmet with her name stenciled on the back. It hangs on the wall, not because she died in the line, but because she lived through a different kind of fire — and made it easier for others to walk through the smoke.

There’s no plaque for that. But we remember.

Legacy isn’t what you put your name on. It’s what others carry forward because of how you showed up when it counted.

Sara never asked to be a symbol. But symbols don’t get to choose how they’re remembered.

And here, at Local 1329, we remember her as one of our own — a firefighter, a builder, a quiet force who left the place better than she found it.

Why Her Story Still Matters

It would be easy to treat Sara’s story like a checked box — the first, the pioneer, the one who opened the door. But that’s not how stories like hers work. They don’t end. They ripple.

Every class at the academy now includes women. Some are strong, loud, confident. Others are quiet, unsure, still learning what kind of firefighter they want to be. But none of them walk in alone. Even if they never met Sara, they’re walking through the space she helped carve out — not with a hammer, but with consistency and grit.

We still have work to do. The job is evolving, but it isn’t perfect. Bias hasn’t disappeared. Not all gear fits right, not all comments land kindly. But the difference now is this: no one can pretend it’s not our problem to fix. And that’s thanks, in large part, to people like her who didn’t wait for permission to start improving things.

More than once, I’ve heard a new firefighter say, “I don’t want to be the best female firefighter. I want to be the best firefighter.” And that shift in language? That quiet dropping of qualifiers? That’s the echo of Sara’s time here.

She didn’t kick the door open. She held it, long enough for others to get through.

Her legacy isn’t just a helmet on a wall. It’s woven into the way our crews train, the way we talk to each other, the way we recognize effort — no matter who it comes from.

And if you’re reading this now, wondering if you’ll fit in here — at Local 1329, or anywhere else that demands sweat and courage — remember this: you don’t need to be loud to lead. You don’t need to make noise to be noticed.

You just need to show up. Keep showing up.

The rest will follow.

About This Story

The story of Sara Martin is a respectful composite — based on the real-world experiences of women who were among the first in their fire departments across the U.S., including departments in Texas. While Sara Martin is not a documented historical member of Local 1329, her journey reflects the challenges, resilience, and contributions of many pioneering women in fire service.

This piece was created to honor the spirit of inclusion, strength, and quiet leadership that so many of our sisters in the firehouse embody — often without fanfare. If and when Local 1329’s own first female firefighter is formally identified in our archives, we will proudly share her full story.

Real stories matter. So do the ones that shine a light on what still needs changing.